Climate change adaptation can’t be separated from sovereign debt in the Global South

Egypt, Pakistan and even Ukraine still have to pay IMF surcharges

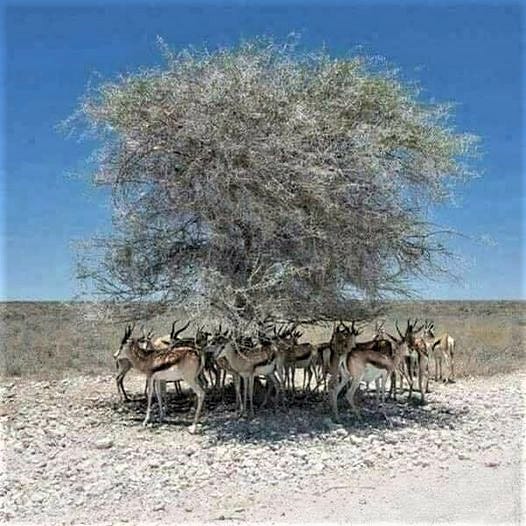

Photo source: X (Twitter.)

The vulnerability of countries in the Global South to the effects of climate change is closely correlated with the risk of debt distress.

That is a key finding of recent research from the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) in Washington. The Growing Debt Burdens of Global South Countries: Standing in the Way of Climate and Development Goals is authored by Ivana Vasic-Lalovic, Lara Merling and Aileen Wu.

The research finds that out of 79 low- and middle-income countries which are in, or at risk of, debt distress, 61 are highly climate-vulnerable. External public debt service in 2023 will exceed climate investment needs in 39 low- and middle-income countries, the authors calculate.

So it’s clear that adapting to climate change can’t be treated as an isolated issue but must be seen in the context of sovereign debt burdens if it is to be effective.

The CEPR makes two key proposals. A new IMF allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), a mechanism used to good effect in 2021 in the Covid-19 pandemic, would be a quick way to provide relief to sovereigns who need financial leeway to implement climate adaptation strategies.

The CEPR also argues that the IMF should abolish the surcharges on its loans to poor countries. These are fees for loans which can add two or three percentage points to the cost of a loan.

Such charges seem a particularly pointless exercise. They do no more than conceal the real effective interest rate on IMF loans. If the IMF needs higher rates, it should communicate that transparently. Pakistan and Egypt, both struggling with increased food costs and climate adaptation, are paying $142 million and $306 million in surcharges per year, while Ukraine still needs to find $316 million a year in the midst of war.